Camp & Bridge

Update June 2015 - This website's domain and web hosting will need renewing within the next year. In order to keep this website online, please consider making a donation of any amount below. We would also welcome any offers from anyone who would be interested in taking the website over. You can contact us at history@wouldhamvillage.com. Thank you.

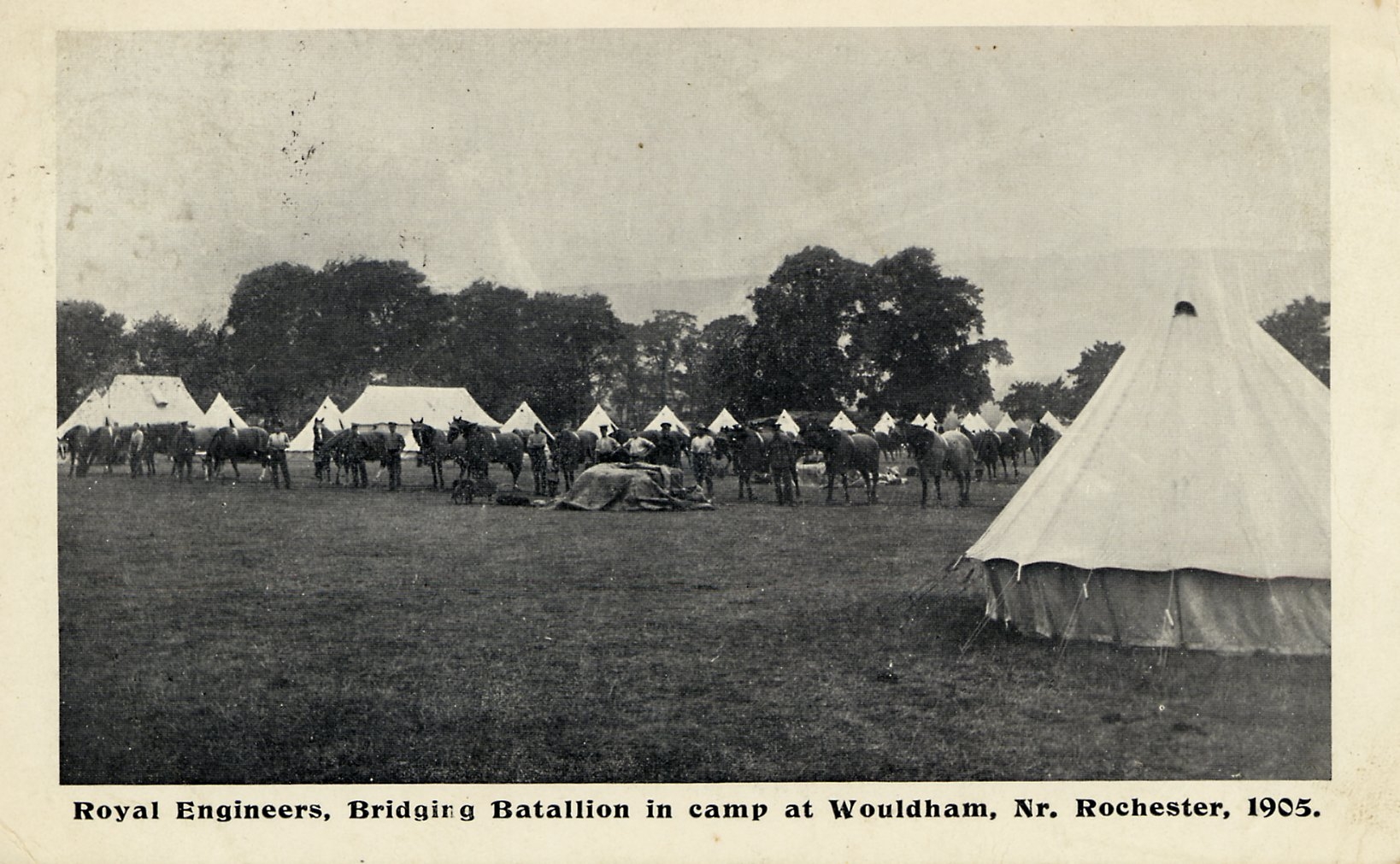

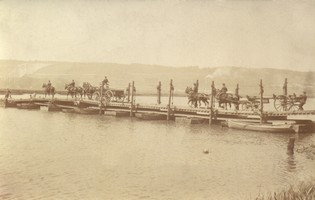

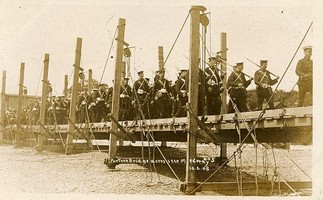

Click on the photo above to enlarge. Photo kindly provided by Snodland Historical Society.

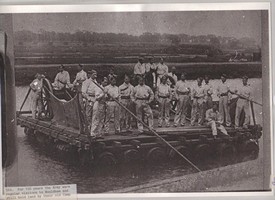

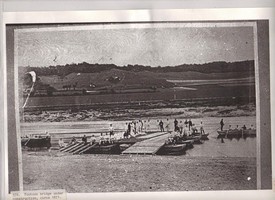

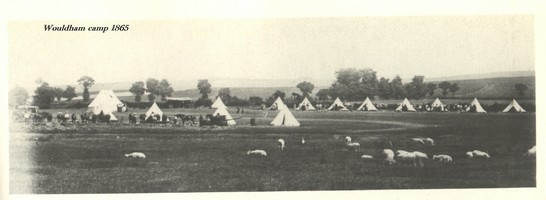

Land was purchased on both the Wouldham and Halling side of the riverside around 1865. This was so that the army could hold summer bridging camps for many years.

One of the disused chalk quarries was used during training for the well known St George's Day Raid on the Belgian port of Zeebrugge in 1918. A replica model of the Zeebrugge Mole was constructed within the quarry and soldiers from the Middlesex Regiment played the part of the enemy.

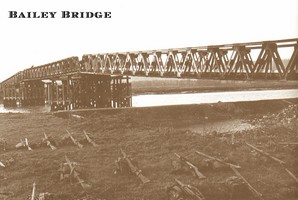

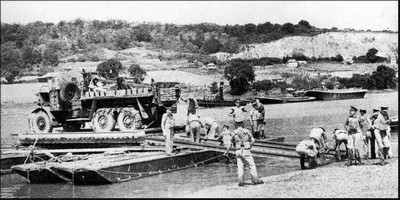

During World War II, the armed forces were trained for the building of bridges which would take place during the Normandy landings. Along with our own armed forces, the American army also came over to learn how to build the bridges.

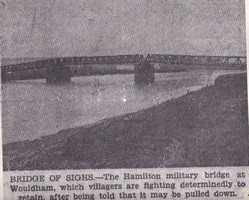

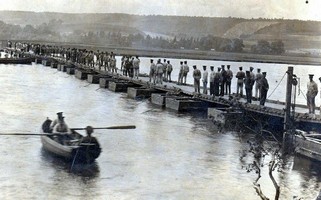

Click on the photo above to enlarge. Photo kindly provided by the Kent Photo Archive.

The bridge of 1941 was the subject of requests from residents to be left in place, but the district council would not pay for the maintenance and industrial users of the river claimed that their barges would not pass underneath during high tide, so it was removed.

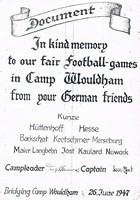

A prisoner of war camp was situated in Wouldham during the Second World War, also at the Bridging Camp, given the camp number of 654a.

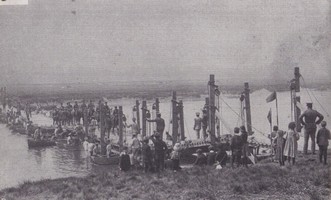

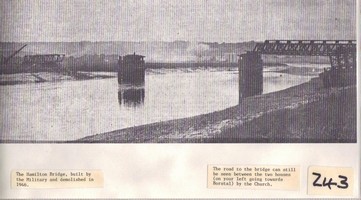

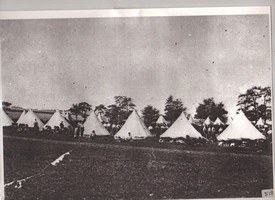

Click on the photo above to enlarge. Photo kindly provided by the Kent Photo Archive.

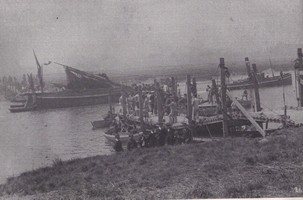

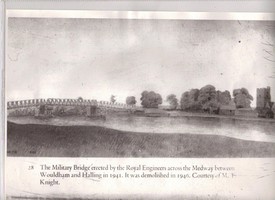

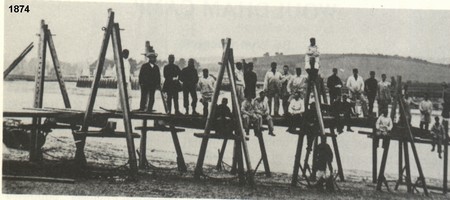

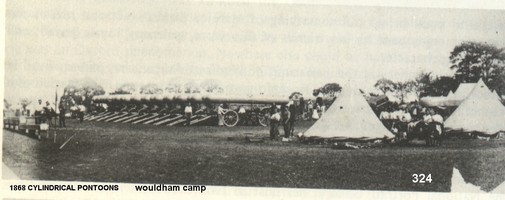

Click on the photo above to enlarge. Photo kindly provided by Imperial War Museums.

Click on the photo above to enlarge. Photo kindly provided by Snodland Historical Society.

Click on the photos above to enlarge. Photos kindly provided by Wouldham Parish Council.

Click on the photos above to enlarge. Photos kindly provided by Roger Webb.

Old Newspaper Reports

Morning Post - Tuesday 18th August 1868

NAVAL and MILITARY INTELLIGENCE. FROM OUR CORRESPONDENTS. CHATHAM, MONDAY. Major-General Freeman Murray, accompanied by Major Lynch, brigade major, left Chatham Barracks this morning to proceed to Wouldham, to make the inspection usual on troops arriving in the district, the A troop of Mounted Engineers having last week arrived at Wouldham, from Aldershot, to go through a course of pontooning on the river Medway, between Cuxton and Wouldham, a pontoon hard having recently been made at Cuxton by a body of Royal Engineers, for the use of the corps. The A troop numbers nearly 200 officers, non commissioned officers, and men, about 140 horses, and a train of waggons. Four officers arrived with the troop - Captain Micklem, and Lieutenants Blood, Sir A. W. Mackworth, and De V. Brooke. The troop, with a body of men from the Royal Engineer establishment at Brompton Barracks, the whole numbering about 300 men, are encamped in a field at Wouldham, occupying about 50 tents, ranged in five rows, the horses being picketed. Wouldham is situated a few miles from Rochester. Major - General J. L. Simmons, C.B., director of the Royal Engineer establishment, and other officers, were present at the inspection.

Corporal Michael Bolger, of the 1st battalion of the 15th Regiment, died very suddenly on Saturday night, falling down dead in his quarters. Corporal Bolger was assistant schoolmaster for the 1st Depot Battalion. Deceased was the weakly constitution. He was an old soldier, and would shortly have been pensioned, he having completed 21 years' service.

Captain R. Berkeley, of the 20th Regiment, has joined the depot at this garrison, from the service companies, who are serving in Canada. Captain Berkeley replaces Major Ledgard, who recently embarked for Canada to join the regiment.

Captain Wilis, of the Chatham Division of Royal Marines, has received leave of absence till the 19th Sept., but if required he is to be present with the division on it's inspection by the Lords of the Admiralty and the inspector-general. Ensign Booth, of the 10th Regiment, has been granted leave till the 14th Sept. on private affairs.

Maidstone Telegraph - Saturday 13th August 1870

FUNERAL OF LIEUTENANT TURNER, ROYAL ENGINEERS.- The funeral of Lieutenant C.E. Turner, Royal Engineers, who was accidentally drowned at Wouldham, took place on Friday afternoon, and was conducted with full military honours. The body was conveyed from Brompton Barracks to Trinity church, on a gun carriage, preceded by the bands of the Royal Engineers, the 23rd Royal Welsh Fusiliers, and Royal Marines Light Infantry, playing at intervals the "Dead March," in Saul, with muffled drums and the instruments draped in black. In advance of the procession marched a firing party of the Royal Engineers, the body being followed immediately by the friends and relatives of the deceased, the procession being brought up by nearly the whole of the officers of the Royal Engineers, and many of those belonging o the various corps in the garrison, including Major - General J. W. Brownrigg, C.B., and Colonel T. L. Gallwey, Commandant of the School of Military Engineering. After the funeral service had been performed in Trinity church, the funeral procession proceeded to Gillingham cemetery, where the interment took place, the firing party discharging the usual number of salutes over the grave.

The Daily News - Wednesday 16th September 1874

THE CAMP OF THE ROYAL ENGINEERS AT WOULDHAM.

This camp is situated in a picturesque spot sheltered by hills, about three miles above Rochester- bridge, on the right bank of the River Medway. It is formed during the summer months for the purpose of instructing the young Sappers of the Royal Engineers in the construction of pontoon bridges, rafts, and in rowing, as well as for the purpose of insuring them to the inconveniences of camp life. The camp was temporarily closed this summer, on account of the absence of the instructor in the field fortification, Colonel Leahy, and his assistants, at the School of Military Engineering in Germany, where they were present for the purpose of observing the pontoon operations on the River Elbe. The camp is square in form, and tents being pitched in parallel rows, at right angles to the river. The entrance to the camp is by a gate on the north-east. The men's tents are pitched on the northern and southern sides, the east side being occupied by the guard-tent, non-commissioned officers' mess, orderly room, and the telegraph office, which is superintended ny the telegraphists of the corps, and by means of which direct communication is kept up with headquarters at the School of Military Engineering, Chatham. The interior space is used as a parade-ground, the lower end of which is enclosed for the accommodation of stores. The water supply is furnished from a well, excavated by Sappers, continuous to which the cookhouse, where the men's food is cooked in a "broad arrow" field kitchen and two of Soyer's portable field stoves. There is a drying-shed attached for the purpose of drying quickly the clothing of such men as may happen to get immersed while at work on the river.

The detachment at present in camp consists of an officer's class, and the 36th and 37th depot companies, comprising Nos. 60, 61, and 63 field work squads. The camp is under the chief command of Colonel Leahy, assisted by Captains Sale, Marsh, and Skinner. The duty of camp sergeant - major is performed by Sergeant- Major Cottrell, and Company Sergeant- Major Christie is in charge of stores.

The detachment parades each morning in canvas clothing about six o'clock, formed up in squads under Quartermaster- Sergeants Cooper, Smith and Burton, and proceed to the Hard, where the drill is conducted under the superindence of Captain Sale. The drill is conducted on the men's part with perfect silence, the words of command being clearly heard on the river by means of speaking -trumpets, and the enforcement of the rule ensures the operations being conducted with alaority. The cylindrical pontoons of General Blanshard have been suspended by the new service pontoons, and it is in the use of the letter that the men are now especially instructed.

The new pontoon is a boat with similar decked ends, and is partly decked at the sides, where eight rowlock blocks are fixed. The undecked portion is 14ft. 8 1/2in., by 4ft, 1 1/2in., and is surrounded by coamings 5in. high above the deck. The extreme length of the boat is 21ft. 7in.; it's extreme breadth is 5ft. 3in., and it's depth amidships, including the coamings, is 2ft. 8in. The pontoon weighs dry about 7 owt., and draws, when floating empty, 2 1/2in., and when in bridge 6in. Each inch of immersion gives about 500lbs. of buoyancy. The pontoon consists of six sets of framed ribs, connected by a deep kelson, two side streaks. The sides and bottom are of thin yellow pine, with canvas secured to both services by india-rubber solution. The canvas is coated outside by two coats of "knotting." An iron ring is attached to the framework at each end, and connected with the kelson by an iron rod. There is a clest for securing the cables to the deck at each end. The bottom is provided with two plugholes to let water out. It is protected outside by five longitudinal battens; on each side of the boat there is a side rail, to which are secured eight handles, by which the pontoon can be carried by hand. There are four thwarts which support a saddle beam, which can be moved when the pontoon is to be used for ferrying troops. The pontoon bridge is formed of pontoons kept at 15ft. central intervals by baulks, fitting on to saddles, resting on central saddle beams. The number of baulks used is five for the "advanced bridge" and nine for the "heavy bridge" for siege artillery. They support ohesses, which are kept in position by a riband on each side, fastened by rack lashings to the outer baulk, and leaving a clear roadway of 9ft. It was calculated that pontoons should not be immersed to within 6in. of the tops of their coamings when carrying such a load as a 64- pounder gun, which weighs 99 1/4 owt. The saddle-beam is fastened to the thwarts by iron pins. The saddle-beam is hollow, 10ft. 1 in. long at the bottom, 9ft. 9in. long at the top, 8in. deep, and 4in. wide. The top is beech wood, the rest is Baltic fir. Its weight is 44lbs. A pontoon saddle is a framing 10ft. 7in. long, 8 3/4in. broad, and 4 1/2in. in depth, which fits over the saddle beam. The saddle has five sets of curved cleats 10 3/4in. by 2in., at equal distances, to receive the ends of the baulks. There are four other sets of cleats, with square ends, placed intermediately to receive the ends of the additional baulks necessary for the passage of seige guns over the bridge; there are handles at each end to enable the saddle to be lifted. The side rails, 10ft. 7in. by 2 1/8in. by 2 1/4in., are of Baltic fir, and the remainder of American elm. The saddle weighs 41lbs. The baulks are of Kawrie pine, 15ft. 9in. long, 3 in. wide, and 6 in. deep. The ends of the baulks are halved in order to lock the saddle, but they are strengthened by iron plates at the top and bottom; the bottom plates are made with two claws to prevent the baulk slipping off its saddle. A baulk weighs dry 71lbs. The chasses are single planks of Kawrie pine, 10ft. long, 1 ft. broad, and 1 1/2in. deep. A chess weighs dry 50 1/2lbs. The ribands are also made of Kawrie pine, 15ft. 9in. by 3in. by 6in., halved at each end, with fourteen buttons. The buoyancy of the pontoon bridge is sufficient to admit the passage of siege artillery and steam sappers, such as are made by Messrs. Aveling and Porter, of Rochester.

The methods of constructing pontoon bridges are- (1) by "booming out;" (2) by "forming up;" (3) by rafts, and (4) by "swinging." The most usual way in the British service of making a bridge is by booming out, or connecting the pontoons with the superstructure in succession from the shore, and pushing out until the head of the bridge reaches the opposite bank, the reverse operation being booming in. It has the disadvantage of requiring seven men to work in the water. A good method, is by foaming up, or connecting the pontoons is succession from the head of the bridge, the reverse operation being dismantling. Bridges are made from rafts of two or more pontoons, by moving them into position, and connecting them. By swinging, a bridge is made alongside the shore, and then swung across the river. This is a favourite method in the United States. The bridge is constructed by the Royal Engineers across the Medway at Upnor, on the occasion visit of the Volunteers, was completed by the men of Wouldham by the raft method.

At Wouldham the men are divided into detachments of seven men and one non-commissioned officer or commander. A, B, C, and D detachments constitute the waggon division, and they unpack the pontoon waggons. E, F, G, and H detachments, or bridge division, construct the bridge. I and J detachments look after the anchors and cables on each side of the bridge, while K and L are spare detachments, ready to give assistance wherever needed. Raft detachments are known as M detachments. On the occasion of our visit to the camp we witnessed the process of "forming up" bridge performed by No. 60 squad, under the direction of Quartermaster - Sergeant Cooper, and the celerity and quietness with which the work was done was marvellous. Each man had his particular position, not a word was spoken; and when the instructor called on certain numbers of the detachments to see if they were in their correct places, they simply raised one hand, and dropped it without uttering a syllable. Every now and then we heard the stentorian voice of Captain Sale, through the speaking trumpet, from a cutter on the river, giving commands, which were obeyed with swiftness and precision, and one could hardly credit that this work could be done with such uniformity and absence of confusion; and, after witnessing such a performance, we can fully endorse the sentiments contained in the complimentary order of the acting-commandant which was issued in reference to their work at Upnor.

The instruction in pontooning terminates about 4 o'clock, when the men are dismissed for the remainder of the day. The camp at evening presents a varied appearance. To dispel the monotony of camp life athletic sports are provided. There is generally a cricket match between the officers and Sappers, and other games are indulged in. As the evening advances the men gather in a circle and improvise an open-air concert until tattoo summons all to their tents. Occasionally there are "camp fires", when numbers of visitors patronised the camp, and these meetings are greatly relished, as they foster that "espirit de corpe" which is a great characteristic of the British army.

Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette - Wednesday 3rd July 1878

A DISGRACEFUL MELEE. A fight among a number of men belonging to a company of the Royal Engineers stationed at the camp of instruction at Wouldham, near Rochester, took place on Monday night in the neighbouring village of Borstal. Some were so hotly pressed that they had to jump into the river and swim across to escape from their assailants. In the melee private gardens were trampled over, and walls and fences broken down. The solitary constable in the village was powerless to interfere, but took note of several of the persons concerned, and by this means several men have been arrested. The commandant of the camp has promised that all damage shall be paid for by the company to which the rioters belong, which has been removed from the camp to barracks.

Manchester Evening News - Tuesday 12th September 1871

The Royal Engineer camp at Wouldham, on the banks of the Medway, which has been carried on during the summer months for the instruction of officers and men in pontooning, is to be broken up for the season.

Life at an Army Training Camp by Vernon Ledgard

WW2 People's War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/.

When I was eighteen, I received my call up papers. First I had to go to Leeds for a medical examination, which I passed A1 and then I received a train warrant and instructions to report to Brancepeth Camp near Durham on 7th December 1944. When I arrived at Durham station, there was a Durham Light Infantry corporal shouting for any recruits for Brancepeth to go outside and board the waiting army lorries. As we approached the camp which was just huts, I was surprised to see soldiers with rifles and steel helmets running through a wet field and throwing themselves down every few yards. This occurred to me as not very healthy, but I later found that the throwing yourself down in the cold and wet was the best bit because then you got a little rest.

We were allocated to a hut and told to put our belongings on one of the two tier bunks. I was only able to get a lower bunk! We then had to fall in outside and were given a knife, fork and spoon each, marched to a long dining room full of very noisy solders all clad in denims, which were the working uniform of the time. We queued up and received a meal of re-constituted potato, boiled tasteless haricot beans and a piece of tough stringy meat. Even so, the men around were shouting for us not to throw anything away, but to scrape it onto their plates. Outside the hut was a large tank full of boiling water to plunge our eating irons in to wash them. We were then marched back to our hut for a first night on a hard camp bed with a pillow filled with straw and three army blankets.

Reveille was at 6a.m. followed by a difficult shave in a room full of jesting squaddies, some of whom used cutthroat razors. Later, we were taken down to Brancepeth Castle to the stores where we were issued with two Battle Dress Uniforms, an overcoat, respirator, rifle, bayonet, denims, two pairs of boots and all accoutrements required for soldiering. Then to the barbers where our heads were shaved to a stubble.

Everyday following, we were rushed from pillar to post, never having a minute until lights out at 10p.m. Continual rifle drill, physical training, Bren gun (a light machine gun) training and marching at a very fast pace at all times. Saturday mornings we were inoculated against various diseases, each man stood in a queue with a bared arm into which was plunged a large blunt needle. Some men fainted. Our arms were very sore and tender for the weekend but when Monday came along it was more marching, rifle drill etc.

It was bitterly cold and I never seemed to feel very well or to be able to get warm.

One day there was a terrible blizzard with a biting north wind; this happened to be our day for a five-mile run in P.E. kit. We ran from the camp gate for two and a half miles west with snow caked on our right side and when we turned to come back, this melted and we received the snow on our left side. We were absolutely frozen, but it was immediately back into denims and out on the square for drill wet or not.

I had to attend the dentist for treatment, which resulted in a tooth being pulled out. All day long it kept bleeding and when I lay on my bunk at night, it still bled so I had to get up to report to the Medical Orderly room. It was a cold clear night with several inches of snow on the ground and I left a trail of drops of red blood in the white snow. I knocked up the corporal on duty and after inspecting the bloody hole in my gum, he rang for a medical officer who came and plugged the hole with cotton wool and instructed me to stay the night in the medical centre. This seemed heavenly, as it was a lovely soft bed with clean white sheets and white pillows.

One day we were issued with two Mills Fragmentation bombs. They looked like a metal pineapple with a locked metal handle on the side. We had a forced march in full kit with rifles, respirators, steel helmets etc. to the throwing ground. It was a bitterly cold day and because of our march, we were sweating when we arrived, we then had to wait our turn to go into the sandbagged throwing bays. The throwing bays had two N.C.O.'s in them and they took two men at a time to throw the grenades. For some uncanny reason, when my time came - we were all sat shivering - I invited the man next to me to go before me. Of course his hands were frozen with cold and he dropped his grenade in the mud, it exploded, resulting in both soldiers and the N.C.O.'s being taken to hospital with severe shrapnel wounds.

I spent a miserable six weeks at Brancepeth camp having infantry training and it seemed like years. The harsh regime was obviously designed to turn callow youths into soldiers, irrespective of the price, which in some cases caused some youths to attempt suicide.

It ended with my transfer to the Royal Engineers and I duly received a railway warrant to report to Kitchener Barracks in Chatham, Kent for a three months training course. The rail journey took me first to London on a packed train. I was in full kit with my rifle and kit bag containing much of my spare clothes and equipment. Most of the time I was unable to get a seat so I sat in the corridor on my kit bag. The change of stations in London meant that I had to use the underground, once again standing room only and I seemed to be carried along by the crowd, packed like sardines in the carriage.

On arrival I was allocated to Boys' Block. This was the oldest part of Kitchener Barracks, comprising large rooms with thirty double tier bunks in each. The ablutions did not have any hot water, this meant shaving and washing in cold. It was all very strange and I felt very lonely and homesick. Once you were called into the forces in wartime, you had no rights whatsoever. You were in for the "Duration of the present Emergency" and the possibility of being able to go back home seemed very remote, if ever. You were constantly told that you are in the army now and you have no rights. If you were given any leave it was a privilege and unless you passed your training course you would have to retrain all over again until you passed. The psychological effect of this on a naive callous youth of eighteen was devastating and depressing. We all received continual severe harsh treatment.

The weather, too, was severe, very cold with some snow on the ground, we were, firstly, to spend our days in an area called the Great Lines, where we were taught how to erect barbed wire and lift or lay mines. Then we had lessons on constructing a bridge across a ravine using heavy posts, somewhat larger than telegraph poles. Most of the men were unused to physical work and found this terribly hard. In my case I was 5'6" weighing only 8st. 4lb. (8 stones, 4 pounds - 1 stone = approx. 6.3 Kg. 1 pound = approx. 0.45 Kg.) and I was not very strong.

Reveille was at 6a.m. with lights out at 10p.m. and you can be sure that we were glad to be in bed at 10p.m. First thing in the morning after washing and dressing, we took our eating irons to join a long queue of sappers outside the cookhouse, the food was appalling, possibly because when women were called up, if they had no skills and were not very intelligent, they were put to work in the cookhouse. They wore a sort of snood on their heads, a pair of clogs and a mainly dirty wrap-around overall. Their interest in the job or the quality of food was, of course, nil. I remember our evening meal was at onetime, fried liver that had been fried to such an extent that it was like leather, this with a dollop of gravy over it. Next morning, we had the same meal heated up for breakfast.

We were allowed out of the barracks in the evening after cleaning our kit and rifles and after blancoeing our webbing and cleaning our brasses. We, then, made our way into the town centre of Chatham which was not far away, our main purpose was to get more food, often egg and chips or sandwiches, kindly sold at the Salvation Army Canteen or the Church Army, manned by volunteer ladies who were most kind to us. We, also, had a NAAFI within the barracks, which supplied these types of meal.

After some weeks we were given training in the erection of Bailey Bridges which were made of heavy steel panels and girders, and finished with a layer of wooden transoms for vehicles to run on. These were quite ingenious as they could be put together quickly and in various ways and at maximum were able to carry heavy tanks. Once we had trained to an adequate standard, we were taken to a place called Wouldham. This was a camp of Nissen huts, which had concrete floors. It was alongside the Medway, a tidal river. There weren't any bunks and we were allocated three blankets and a straw filled pillow and had to sleep on the concrete floor. The toilet was a wooden beam suspended across a stinking pit in the open air. Our dress was denims, U.S. boots (unserviceable) and no socks. Steel helmets were worn at all times.

On our first morning, we were introduced to the Medway. The beach had been formed by tipping a thickness of large pebbles. At the top were some very heavy pontoons (flat top boats), it took about a dozen men at each side to lift them and slowly take them to the river. The sergeant in charge bellowed that they must be taken into the water until they floated. If the bottom scratched the pebbles, we had to lift them back to the top of the beach and do it all again. Obviously, the leading men had to go into the freezing water up to their knees, that's the reason for no socks. When the pontoons were floated, we then had to clamber on board, insert a large oar and with our feet braced against a wooden cross piece, sit on the flat deck to row. At the order of "Up Oars", the oars had to be raised to vertical position, standing between our thighs. Of course the water ran down the oar, which meant that we were sat in a puddle. All this was in freezing weather.

We had training in building various types of pontoon bridges at night in blackout, no lighting whatsoever. The only good thing about this two-week course was that we were allowed double rations and we had some very good men cooks who did an excellent job. The food was superb!

As you can imagine, all this type of training resulted in many casualties, frozen fingers, slipping off cold steel transoms etc. letting heavy weights fall onto legs, feet or hands. The working parties (as they were called) consisted of a hundred and twenty men, and of these we had more than twenty casualties by the end of the three-month course. In my case, I suffered from frost bitten hands; my fingers were cracked, bleeding and severely swollen.

Our next severe test was a live ammunition assault course. We were taken to a large overgrown unused quarry and assembled at the entrance. As we stood waiting, our anxiety increased because of the tremendous row going on within, loud explosions and the constant chatter of Bren guns. I had become friendly with Norman Horton a young man from Brentford, and another young man called Eddie always attached himself to us when things got difficult or frightening. This was certainly one of those times. He told us that he just couldn't face the run, he was completely terrified. We placated him saying that he could run between us where he would be safe. There were Bren guns at the top and both sides of the quarry firing the ammunition over our heads and with continual explosions alongside our route, which took us under barbed wire along channel in the earth, and over specially prepared obstacles. Smoke was everywhere; I shouted to Norman, "Where is Eddie?" Eddie had disappeared. Fear had lent wings to his feet, for when we reached the end where men were lying in the grass panting for breath, Eddie had got there long before us.

In the evening, after this event, we had to spend our time cleaning the mud and filth from our equipment. Cleaning boots, blancoeing our webbing and gaiters (Blanco was a khaki coloured powder and could be purchased in a can, this was mixed with water and brushed onto the webbing). We had to clean our 303 rifles which we took with us at all times when training, these had to be spotless because our first event of the day was a close inspection of equipment. Anyone not having his kit up to standard was put on a charge and had to report to an officer. The punishment was seven or more days being confined to barracks and having to report to the guardroom where you were allocated two hours of chores, such as washing floors, sweeping up debris etc.

Pay for a new recruit was 21/- (21 shillings - one pound and five pence). If you accepted 14/- (70p) and you were killed whilst in the army, your next of kin received a pension. This seven shillings was allocated to your next of kin each week and could be redeemed from the post office. I made this allocation and received pay of just 14 shillings per week.

I was always a thrifty person and in my wallet I kept a large white five-pound note. This was a secure reserve for any emergency, particularly to be able to pay my fare if I could get leave to go home. It was possible to apply for a weekend pass, which freed you for forty-eight hours, Saturday and Sunday. This was fine for southerners who lived around London etc. but as it was a whole day's journey to get to Yorkshire, it was out of the question for me. On two occasions, Norman invited me home for the weekend at Brentford. They were two greatly cherished events, which I thoroughly enjoyed. Norman took me into wartime London and showed me the sights. London was packed with service personnel, particularly yanks. By this time there were no bombing raids but an occasional V.2 rocket could be heard landing with a distant boom, not unlike someone beating a metal drum. No-one took any notice, there was no point, if one landed near, it was just bad luck!

At last, after three very lonely months of training with the Royal Engineers, the course came to an end. I was given ten days leave, starting on Thursday 8th April 1945 until Sunday 6p.m. on the 20th. We received a free return travel warrant to our destination. I was ecstatic! The four months away from home seemed like four years. I took the train to London and the tube to Kings Cross station to catch the 9.45 p.m. to Yorkshire. I was sure that I was the happiest man on earth. I managed to get a seat in one of the compartments. Opposite me was a pale thin soldier wearing what was obviously, a brand new uniform. He had no insignia on this uniform, which was unusual, all uniforms had a regimental insignia on the shoulders, mine clearly showed "Royal Engineers". I was intrigued and offered him a cigarette, which he refused. In the ensuing conversation, I gleaned that he had been a prisoner of war in Germany for some considerable time. He had been in Stalag in the west of Germany and as Russian forces were advancing into Germany, the prisoners were taken out of their camp and marched towards the east. There were no food supplies and he and the other prisoners had to live off anything that they could find. They were marched many, many miles; anyone who fell out would be shot. He survived and was eventually freed by American forces. All the prisoners were little more than walking skeletons and very weak, they were given food but advised not to eat too much as it would be dangerous to put too much into their shrunken stomaches. He informed me, that some men were unable to resist the food and had eaten too much and died.

We reached Halifax station at 5 a.m. This man's wife had received notification that her husband was on his way home and having no idea when he would arrive, she had camped out on the station to meet every train night or day. What a reunion!

From Halifax I shared the cost of a taxi with another soldier who lived within a mile of my home. As it was still dark, I decided to walk the last mile. I was walking on air those last yards. The dawn chorus started and there I was, walking along the old familiar road to my home. I knocked on the door, realising that my parents would still be in bed. Then distant voices; the sound of footsteps coming down the stairs. It was my mother in her dressing gown. She opened the door and her first words to me were, "What are you wanting at this time in the morning?" She did not recognise me, I had gone away a pale callow youth and during my time away I had put a stone on in weight and of course I was in army uniform.

Guestbook

Do you have any comments or want to contact other people visiting the website? If so, please leave a message in our Guestbook.